Contrary to what many think that the Philippines case against China in the Arbitral Court of the United Nations Commission on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) will clarify who owns what or which of the reefs in the Spratlys, it won’t.

Contrary to what many think that the Philippines case against China in the Arbitral Court of the United Nations Commission on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) will clarify who owns what or which of the reefs in the Spratlys, it won’t.

That’s because that is not in the scope of the U.N. Arbitral Tribunal where the Philippines filed the case. The UN Arbitral Tribunal only deals with the interpretation and application of UNCLOS.

It does not decide on sovereignty over disputed features in the sea.

Territorial disputes are the domain of the International Court of Justice or ICJ.

The reason the Philippines didn’t haul China to the ICJ was it requires the participation of all parties in a territorial dispute. China refuses to be a party to an ICJ case. It has always insisted that the best way to resolve disputes is bilateral negotiations.

The Philippines, on the other hand, insists that negotiations should be multilateral – among all claimants in the Spratlys.

The Philippines’ insistence on multilateral negotiations is puzzling in the case of Scarborough Shoal (also known as Panatag Shoal and Bajo de Masinloc. The Chinese call it Huangyan island) because unlike in the Spratlys, which is claimed wholly or partly by five countries and Taiwan, the dispute over the shoal, 124 nautical miles from the shores of Zambales, is only between the Philippines and China.

Since the Arbitral Tribunal does not decide on territorial conflicts, the case filed by the Philippines against China is about maritime rights.

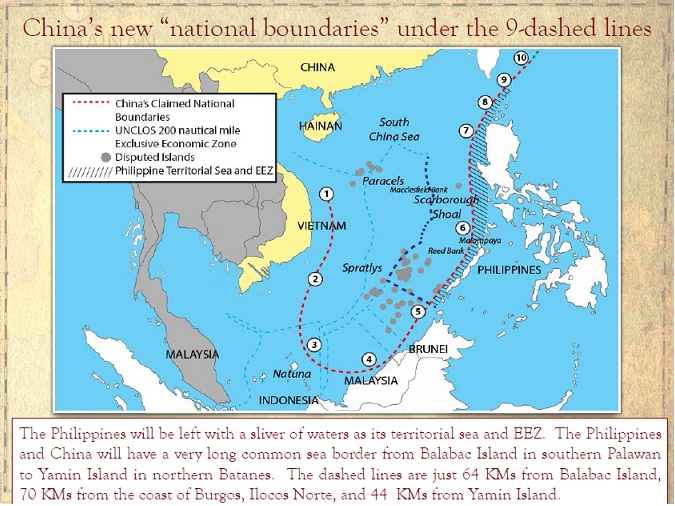

The three basic issues of the Philippine case versus China are: The validity of China’s nine-dash lines; low tide elevations where China has built permanent structures should be declared as forming part of the Philippine Continental shelf; the waters outside the 12 nautical miles surrounding the Panatag Island (Scarborough shoal) should be declared as part of the Philippines 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone.

Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio, who has been doing lectures on the South China Sea conflict, explained “The Philippines is asking the tribunal if China’s 9-dashed lines can negate the Philippines’ 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone as guaranteed under UNCLOS. The Philippines is also asking the tribunal if certain rocks above water at high tide, like Scarborough Shoal, generate a 200 NM EEZ or only a 12 NM territorial sea. The Philippines is further asking the tribunal if China can appropriate low-tide elevations (LTEs), like Mischief Reef and Subi Reef, within the Philippines’ EEZ. These disputes involve the interpretation or application of the provisions of UNCLOS. “

Supreme Court Associate Justice Francis Jardeleza, when he was still the solicitor general in February 2014, also explained to reporters: We are not asking the court to say who owns Panatag shoal. We are arguing that they are within our EEZ and therefore under the rules of UNCLOS we have exclusive rights to fish within that area. For example Mischief Reef, again it’s completely submerged. If it’s completely submerged therefore it is entitled to no rights at all. We are not saying, asking the tribunal to declare who owns the structures above the reefs. All were saying is declare that it being submerged it is entitled to no rights at all. So whatever rights the occupant has is only to the structure. It has no 12-mile territorial sea or even one meter territorial sea. So our claim is a very narrow one, land dominates the sea. This is not a case about land. This is a case about the maritime waters which is perfectly under UNCLOS.”

It’s classic brinkmanship. Even the Chinese are impressed.

In its position paper published Dec. 7, 2014, China said: “The Philippines has cunningly packaged its case in the present form. It has repeatedly professed that it does not seek from the Arbitral Tribunal a determination of territorial sovereignty over certain maritime features claimed by both countries, but rather a ruling on the compatibility of China’s maritime claims with the provisions of the Convention, so that its claims for arbitration would appear to be concerned with the interpretation or application of the Convention, not with the sovereignty over those maritime features. This contrived packaging, however, fails to conceal the very essence of the subject-matter of the arbitration, namely, the territorial sovereignty over certain maritime features in the South China Sea.”

If the Arbitral Tribunal agrees with China’s observation that the case is really a territorial and sovereignty dispute, it would say it’s outside its jurisdiction. That’s the end of the case.

But if the Philippine legal panel headed by the current Solgen Florin Hilbay and Washington-based lawyer Paul Reichler, are able to convince the Arbitral Court that the Philippine case does not involve determination of sovereignty over disputed maritime features, the issue of jurisdiction is hurdled. On to the discussion of the merits of case.

That would already be an almost win.

Be First to Comment