Text and photos Maria Feona Imperial

VERA Files

(First of two parts)

Movies featuring the country’s most popular stars—including presidential sister Kris Aquino, comedian Vice Ganda, screen favorites John Lloyd Cruz and Jennylyn Mercado, and young love team Alden Richards and Maine Mendoza—are likely to make the 2015 Metro Manila Film Festival another smash hit, possibly raking in much more than last year’s almost P1 billion earnings.

But government auditors and MMFF critics say proceeds from the festival, in dwindling amounts, are not reaching their intended beneficiaries on time, and that an accounting of the festival proceeds is long overdue.

MMFF officials, on the other hand, say the festival is a private undertaking not covered by government audit rules and regulations, even if it is run by the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA).

The main issue is the amusement tax collected from Metro Manila theater owners who screen only MMFF entries for 10 days from Dec. 25 until Jan. 5. For that period, the local government units waive amusement taxes in favor of movie industry beneficiaries.

But the MMFF has still to remit some P108 million in amusement tax revenues to its intended beneficiaries. Of that amount, P82,787,440 is from proceeds from the 2002 to 2008 festivals, according to a special audit of the Commission on Audit in 2009. Also still unremitted is some P26 million for the years 2009 to 2013.

Last month, actor and Film Academy of the Philippines (FAP) president Leo Martinez asked chairman Emerson Carlos of the MMDA, which administers the MMFF, to comply with the findings of the 2009 COA audit.

“All that the FAP is asking is for the MMFF Philippines (MMFF-P) Executive Committee to comply with these findings,” Martinez wrote in a letter dated Nov. 9.

FAP is one of four agencies supposed to share half of the MMFF proceeds. It is supposed to get 20 percent, the Motion Picture Anti-Piracy Council another 20 percent, the Film Development Council of the Philippines 5 percent, and the government-run Optical Media Board 5 percent.

The other half is supposed to go to the Movie Workers Welfare Fund (Mowelfund), a 5,000-member nonprofit organization founded by former actor and producer, former president and now Manila mayor Joseph Estrada for the welfare of workers in the movie industry.

As of a week ago, beneficiaries like the FAP had still not received last year’s tax revenues in full. Martinez said the MMDA still has a balance of P1 million for MMFF 2014.

“Why is it that while the MMFF gross ticket sales are growing, the amount received by the beneficiaries is decreasing?” Vinarao said.

The answer apparently lies in the fact that the MMFF can make up the rules as it goes along, and that year after year, those rules can change. In 2013, for example, the MMFF created a rule allowing the festival organizers to utilize the amusement tax before it is distributed to beneficiaries.

“All amusement taxes, other than non-tax revenues shall form part of the MMFF fund, and shall be released to the designated beneficiaries after deducting all the operational and incidental expenses of the MMFF,” says what is called Rule 10 of the MMFF 2013.

MMFF executive committee member Dominic Du said 75 percent of the money collected is given to the beneficiaries. Around 20 percent is allotted for the prizes and 5 percent to augment operating expenses.

The MMFF’s expenses include holding the Awards Night and giving out prizes for, among others, Best Picture, Best Actor and Actress, Best Float, Best Director. Compensation for receptionists and usherettes, and logistical expenses during meetings also form part of the operating costs, Du said.

Rule 10 has been there long ago, he added, but it was only put down in writing in 2013.

When Martinez wrote the MMDA demanding an accounting of MMFF funds, it was the MMFF that responded. A two-page letter signed by MMFF Executive Chairman Jesse Ejercito included the breakdown of expenses for MMFF 2013.

Ejercito said the total Metro Manila tax revenues collected during the 10-day festival amounted to P19.7 million. Only P14 million was released to the beneficiaries. P4.7 million was used for the MMFF awards night, P594,000 for the festival’s operating expenses and P500,000 was donated to typhoon Haiyan victims.

Ejercito also rejected the idea that the FAP had a right to demand an accounting of the MMFF fund.

“Our position is consistent with the law and existing jurisprudence, where the right to demand accounting may be exercised only by the trustors over the trustee (MMFF), which in this case are the Metro Manila local government units (LGUs),” the letter read.

“If I’m only helping you and you’re only benefitting from what I give you, do you have the right to demand how I spend the money?” Du said.

Martinez finds this unjust, saying any citizen can question and demand an accounting from the MMDA, given that amusement taxes are public funds.

According to Martinez, of the P14 million that was given to the beneficiaries in 2013, 20 percent or P2.8 million was allocated to FAP. The first tranche was P1 million, while the P1.8 million balance was divided into five tranches and given every other month. Martinez said FAP received the last tranche in January 2015—a month after another the festival.

“They are taking advantage of our money. Why would they earn from it? They do not give it immediately even if they already have it 20 days after the last day of the festival,” he said of the MMDA.

For the longest time, the MMDA has not been held accountable for the delayed and incomplete disbursements, Martinez said.

Lawyer Gloria Galanida-Calvario, supervisor of the COA special audit of MMFF funds from 2002 to 2008, said the MMDA should follow the specified distribution scheme for the beneficiaries, which means that the MMDA should not touch the money.

“Under the law, the MMDA is just a trustee,” Calvario said, pertaining to the MMC Executive Order 86-09, the law that created the MMDA’s operation and management of the film festival.

Calvario said Rule 10 defeats the MMFF’s purpose, which is to provide funds for the “benefit of actors, actresses and people who work behind the camera.”

Du and MMFF spokesperson Marichu Maceda said the entire issue is a mere case of conflicting interpretations of the law. Du said the awards are also given to industry players, who can be considered beneficiaries.

“It’s an incentive, to encourage them to do better,” Du said.

Maceda said while these incentives in the form of awards make the festival “more commercial,” she firmly believes that they are needed to make the festival survive.

“That is how we interpret the EO that created the festival. We can deduct from there to give out as rewards to deserving industry people,” Du said. “But the FAP can’t, so let the court decide.”

Du said it is better to wait for the court’s decision on whose interpretation is correct.

Last year, Martinez filed a petition before the Quezon City Regional Trial Court to compel the MMDA to release the P82 million balance of tax revenues. The case hasn’t been moving, and its scheduled hearing on Sept. 19 was canceled due to stormy weather.

The MMFF representatives also maintain they should not be subject to audit by the COA to begin with. Maceda said the Department of Justice considers the MMFF a private entity. “So by law, COA has no authority over private companies,” she said.

“We have our own auditor. COA is to audit only government,” she added.

However, Desiree Aquino, leader of the team who performed the 2009 special audit, said the portion of the funds that is subject to audit is amusement taxes.

Even if MMFF is a private entity, the amusement taxes from the LGUs are government funds, Aquino said.

Beneficiaries question use of MMFF funds

(Conclusion)

THE decade 1975 to 1985 could be considered the golden years of the Metro Manila Film Festival, when it produced such classics as Ganito kami noon, paano kayo ngayon by Eddie Romero, Minsa’y isang gamu-gamu by Lupita Kashiwahara, Ina ka ng anak mo by Lino Brocka, Kisapmata by Mike de Leon, Himala by Ishmael Bernal and Brutal by Marilou Diaz-Abaya.

These days, the MMFF is associated with films that recur every year in a seemingly endless loop, at one point featuring the same stars and themes that hardly reflect the original objective: “To encourage quality film production both in substance and in form.”

One of the differences between then and now—aside from the quality of the films produced—is that all the MMFF’s proceeds used to go to the film industry rank and file, benefiting and invigorating the thousands of nameless behind-the-camera workers.

From 1975 to 1985, the sole beneficiary of the MMFF proceeds was the Movie Workers Welfare Fund (Mowelfund), a foundation established in 1974 to provide aid to movie workers “in times of sickness, disability, accident and death.”

Mowelfund’s annual share from the MMFF used to be around P16 million, enabling it not only to provide for its members’ medical and health needs, but also to send at least 10 scholars to prestigious film schools abroad, according to Mowelfund education director Edgardo Vinarao.

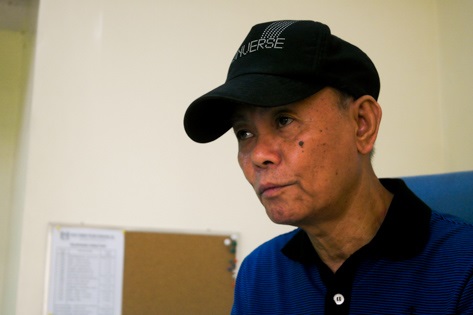

The 70-year-old Vinarao considers the 1980s to be the best years of Mowelfund, when it would receive homage from renowned film scholars it sent abroad and from the countless movie workers who had sought financial assistance to send their children to school, their spouses to work, and themselves to the doctor for chronic pains.

Even if the film industry didn’t pay much, he said, Mowelfund was able support thousands of movie workers because funding from the annual MMFF, the highest-earning film festival in the country, was sufficient.

Caught in a tight budget, the seven-story Mowelfund hub in Quezon City is a shell of what is once was, with no homecomings of successful filmmakers taking place and no movie workers paying frequent visits. Only half of the dimly lit building is being used, with some of its office spaces now leased for commercial purposes.

One of the reasons Mowelfund has been getting less from the MMFF over the years is that the festival rules are constantly changing, depending on who sits in the MMFF and the Metro Manila Development Authority.

In recent years, the changing rules have resulted in a smaller allocation to Mowelfund which now shares the proceeds with other film industry groups, and in amounts that have been dwindling.

On top of that, the MMFF fund intended for beneficiaries is also used for other expenses.

The MMFF has two sources of funding: tax revenues or amusement taxes, and non-tax revenues.

Tax revenues come from the amusement taxes theater owners would have normally paid to local government units. But for MMFF’s 10-day run from Dec. 25 to Jan. 5, Metro Manila’s local government units waive the amusement taxes in favor of MMFF beneficiaries.

Under a 2010 directive from the Office of the President, Mowelfund should get half of the collected tax revenues from the MMFF. The remaining half is divided among the Film Academy of the Philippines, 20 percent; Motion Picture Anti-Piracy Council, 20 percent; Film Development Council of the Philippines, 5 percent; and the Optical Media Board, 5 percent.

In recent years, though, these beneficiaries say they have not been getting their full share of tax revenues from the festival, forcing them to hold horseracing contests, fun runs and golf matches to raise funds.

Meanwhile, the MMFF’s non-tax revenues are supposed to come from the bonds, royalties and penalties incurred from participants in the festival.

MMFF executive committee member Dominic Du said the MMFF no longer generates non-tax revenues. In the early years of the festival, he said, contributions, donations and sponsorships were enough to cover operating expenses.

But times have changed. “For the past few years, it’s been difficult. The sales are bad,” Du said.

Because of this, the MMFF is forced to draw on the tax revenues even for its operating costs and prizes, taking from what should go to movie industry beneficiaries.

The Commission on Audit says the MMFF’s tax revenues should be deposited in trust for its beneficiaries and are subject to government audit. The non-tax revenues, meanwhile, are supposed to shoulder the operating costs, prizes and awards.

When a certain film applies for a slot in the festival, its producers are required to pay a certain fee, said MMFF spokespeson Marichu Maceda.

Once selected, every participant must give a bond of P750,000. Should they back out before the festival starts, the amount will be forfeited by the MMFF for “depriving somebody else who could have gotten in of that slot,” Maceda said.

Created by President Ferdinand Marcos in 1975 to foster “cultural awakening under the New Society” during the martial law years, the festival was first called the Metropolitan Film Festival, and was timed for around Sept. 21, the anniversary of the declaration of martial law.

The festival was organized “in recognition of the value and importance of the local movie industry in the overall developmental effort for the country, a fitting celebration to encourage quality film production both in substance and in form, as well as provide incentives to the performing artists and the technicians in the industry,” according to Proclamation 1533, one of the many edicts Marcos issued in relation to the film festival.

The proclamation also created an executive committee that would oversee the festival, which eventually came under the Metro Manila Commission (MMC).

The MMC had legislative and regulatory functions in the then newly constituted Metro Manila area, with former first lady Imelda Marcos as governor, and the late Ismael Mathay as vice-governor. It would be later renamed the Metro Manila Film Festival, and would go through many evolutions through the different presidential orders issued in relation to it.

The constantly changing MMFF rules have resulted in an inconsistency in delivering proceeds to intended beneficiaries, and in what is believed to be the use of the MMFF fund for other purposes. At one point in 2009, Sen. Jinggoy Estrada even delivered a privilege speech exposing how part of the MMFF fund allegedly went to then MMDA chairman Bayani Fernando as cash gift for his birthday.

The unending controversies over the MMFF have prompted calls for the transfer of the festival’s management to Mowelfund from the MMDA. In the 15th and 16th Congresses, Estrada and other lawmakers filed bills giving Mowelfund control of the festival. These bills have not been approved.

MMFF spokesperson Marichu Maceda said private entities like Mowelfund can’t do it alone.

“There have always been groups within the movie industry who feel that it is they who should be running the festival,” she said. “What they don’t know is that you will need the influence of the government to run this successfully.”

Maceda said the role of the MMDA in the festival is crucial, especially in seeking cooperation among Metro Manila mayors in the donation of amusement taxes.

She also said the “biggest stakeholders” of the festival are the theater owners and producers. “We cannot run this fest without the cooperation of theater owners. You have to be on good terms with theater owners, otherwise, you can be pulled out from the festival,” she said.

However, FAP president Leo Martinez said the festival has long been under the control of theater owners and producers who make the most profit.

For the next two weeks, Filipino films will again dominate the screens in Metro Manila. But for the nameless ones who helped put them there, the movie workers in charge of the dirty work, it is a question of when their plight would take center stage—or if it ever will.

“It’s pitiful how those who are hoping for benefits do not get them,” said Vinarao. “At a time when the nation is impoverished, the film industry is earning much. Why don’t they give it to the poor?”

(VERA Files is put out by veteran journalists taking a deeper look into current issues. Vera is Latin for “true.”)

hindi na film festival ngayon kundi trash festival na. and that started nu’ng babuyin ni lolit solis ang awarding sa FAMAS nang pakialaman niya kung sino dapat ang manalo ng best actor and actress award.

panahon ngayon ng komedyang kababalaghan. ang sumisikat ay mga mukhang baklang tikbalang.

kahit saang larangan, pulitika lalo’t may kinalaman sa pera. mga beneficiaries ng film festival ay nagmimistulang mga pulubing namamalimos ng awa upang amutan ng mga timawang namamalakad sa MMDA. mga suwapang!

art. sining. yan ang sentro ng festival, ng MMFF pero mas nagiging sining ng kababuyan at kurakutan.

wala na ang mga makabuluhang pelikula. wala na ang matitinong artistang iginagalang sa industriya. wala na din ang mga direktor na ang mga obra ay maihahanay sa pandaigdigang criteria na kapupulutan ng magagandang aral at/o mahahalagang bahagi ng mga pahina ng ating kasaysayan.

balewala na ang moralidad na dapat ipamulat sa mga kabataang siyang pakay ng mahuhusay na obrang inilalahok sa festival at mas nangingibabaw na kinang ng salaping kikitain ng mga prodyuser at may ari ng mga sinehang may monopolyo sa industriya.

Simula nung maliit na paslit pa ako hanggang sa ngayon, hindi yata ako nakapanood kahit isang pelikula diyan sa MMFF. Una, pinagbawal ng Dad ko na manood kami ng pelikulang Tagalog. Pangalawa, wala naman yatang nagbago sa atake ng mga pelikula sa mga issues na matitino. Usually yung magandang mga istorya – yung mga makabayan – nilalangaw sa takilya. Inaabangan ko na lang sa TV.

Pero nakaugalian na naming manood ng Parade of Stars sa Roxas blvd. dahil malapit lang sa amin.

Ang alam ko, taon-taon nagdadagdag ng singil ang MMFF para sa Flood Control. Ayun, wala nang baha diba? Meron pa ba? [wink][wink]

Tongue, maraming maganda in the last MMFF compared the previous MMFF. I watched “My Bebe Love.” Masaya.

I missed Honor they Father. Maganda daw.